Painting//War

Roy Uptain

February 6, 2023-March 8, 2023

Uptain’s paintings explore the competing ideologies that create, circulate, and display images in times of conflict. Through his use of multiple perspectives (a war photographer’s lens, a military spy plane, a videogame screenshot, a cell phone photo), Uptain questions the unseen forces that shape public opinion, seeks ways to better understand our historical moment, and explores more authentic ways to bear witness to each other's experiences.

A former public affairs specialist for the Army National Guard, Uptain’s interest in photojournalism began during my training from 2019-2020 at the Defense Information School.

“We were taught to frame each narrative around command-approved talking points, control the backgrounds of photos so as not to reveal government secrets, and edit out the faces of special government operatives,” said Uptain. “This fueled my fascination with the methods special interest groups, like the military, use to manipulate public discourse and deceive their audiences.”

Being privy to methods the military uses to construct public opinion and shape foreign policy motivates Uptain to examine images of war more closely.

Through the paintings in this exhibit, Uptain explores images of the ongoing war in Ukraine and the impact they could have on its participants and spectators.

The exhibit offers a unique artistic experience and seeks to start a conversation about the war in Ukraine and how we narrate our role as spectators to that conflict. 20% of all sales will be donated to United24, a global digital initiative founded by Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy to raise funds and support Ukraine amid the Russian-Ukrainian war.

Join us at Scarlow’s Gallery in downtown Casper from February 6th to March 8th for a thought-provoking and visually stunning exhibit by Roy Uptain. A reception and artist talk will be held at 2:00 PM on February 25th for those interested in learning more about the artist, his process, and this series of paintings.

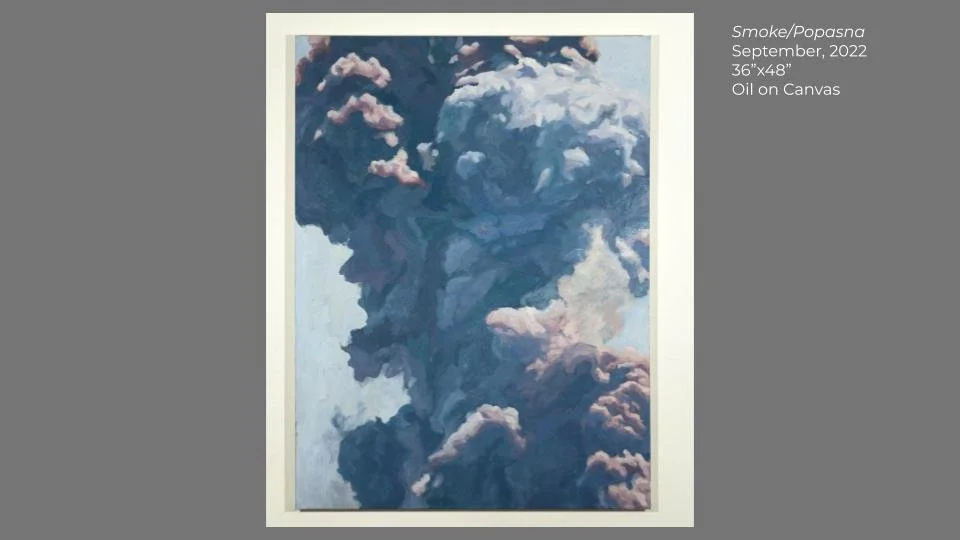

Smoke/Popasna

36"x48"

Oil on Canvas

September 2022

On July 2nd, 2022, the Ukrainian Armed Forces destroyed a Russian ammo depot in Popasna in Eastern Ukraine. The video shows a plume of purple, orange and gray smoke billowing up from an otherwise serene landscape.

Watching this video gave me a sense of deja vu–like I had seen this image before and knew I would see it again.

I had seen images of smoke from fires and mushroom clouds from explosions in hundreds of paintings, photographs, and history books.

But most of these images come from news coverage I witnessed while the events unfolded. Some of the most memorable were the smoke billowing from the Twin Towers during 9/11, roiling gray plumes pouring from Notre Dame Cathedral on April 19th, 2019, the mushroom cloud erupting over Beruit on August 4th, 2020, the pops of white teargas exploding around protesters during the George Floyd protests in 2020.

Historically, artists paint clouds to explore concepts at the core of their artistic vision. As Sotheby’s says in an article about Study For Clouds (Contre-Jour) by Gerhard Richter, “Clouds, being clouds, are intangible, shapeless, formless, always in flux. They are a boon for artists who want to symbolize a subject out of their control.”

The same formlessness is true of smoke. The difference between smoke and clouds is composition. Smoke is made up of burning and burnt particulate matter floating in the air. Clouds are made of water vapor.

Clouds signify rain. Smoke signifies fire.

To me, the substitution of serene cloudscapes with smoke (from tear gas, wildfires, terrorist attacks) is a sign of our times––our world on fire.

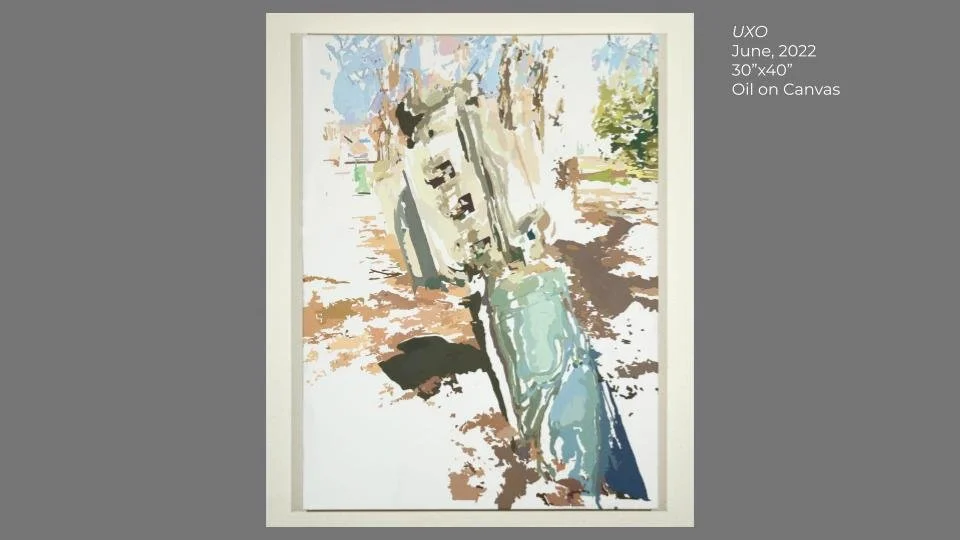

UXO

30"x40"

Oil on Canvas

May 2022

I painted UXO in response to AP photojournalist Andrew Marienko’s photo of the tail end of an unexploded Russian missile that landed in a public park in the city of Chuhuiv, Kharkiv region, Ukraine.

UXO is military shorthand for Unexploded Ordnance. Basically, it's an explosive device that was supposed to go off but didn’t––it's an impotent bomb––which I’ve always found to be a funny kind of an oxymoron.

Unexploded bombs reflect the contradictory combination of immense power and complete impotence within the institutions and individuals that create them.

A uniquely human expression captures this combination: We’re often our own worst enemies.

That is to say, we often cause our own failure––by a lack of self-awareness, inability to accept information that contradicts our assumptions, or just our fundamental human limitations.

That's why UXO are such complex objects for me.

It’s an odd feeling to celebrate failure, but I get a sense of profound relief every time I see a UXO. I think to myself, here is evidence of humankind’s most advanced technological achievements and a failed murder attempt. It's as if God has reached down to hold back Cain’s hand as he prepared to strike Able.

Maybe, In a world filled with chaos and contradictions, celebrating our failure to destroy each other can be a good kind of crazy.

Zed

36"x36"

Oil on Canvas

June 2022

I created an artwork inspired by a photo taken by journalist Felipe Dana. The photo was taken on May 2, 2022, in a village near Kharkiv, Ukraine and shows the bodies of four men lying in the street, arranged in the shape of the letter "Z." This "Z" has been used by Russia as a symbol of its invasion of Ukraine.

I was drawn to the photo because it demonstrates how photography can be used to convey a message about war. The photo shows the destruction caused by the war, the displacement of people from their homes, and the violence of armed conflict.

However, the photo is not easily interpreted. The identities of the people in the photo are unknown. Were they soldiers, civilians, or civic workers? The motivations behind arranging the bodies in the shape of a "Z" are also unclear. Is it meant as a threat, a form of intimidation, or an attempt to discredit one side or the other?

The photo's ambiguity, in a way, makes it even more compelling. It shows that war can rob people of their lives and leave us with more questions than answers. Simone Weil, a writer, once said that violence at its extreme turns people with lives, hopes, and dreams into just dead bodies.

The photograph leaves the viewer with no coherent meaning—only the experience of confusion and loss in the face of the senseless obliteration of human life.

By painting it in simple shapes of color, I attempt to create enough distance from the source photograph to allow space to breathe. In that space, we can grapple with the cruelty humans are capable of inflicting upon other humans.

And we can mourn.

Precipice

36"x36"

Oil on Canvas

April 2022

I painted Precipice in response to a photo by AP photojournalist Felipe Dana captured on April 8, 2022. The photo shows Oleg Mezhiritsky and his mother, Lidiya Mezhiritska, standing on the edge of a crater where part of their home had been before the Russian military began shelling their neighborhood.

I first encountered this photograph in my Instagram newsfeed, along with several others showing the effects of the Russian missile barrage. I searched for more information about the Ukrainians photographed but came up empty-handed.

I began thinking about the journey the photograph took to reach me. It began when Felipe Dana held the shutter button on his camera. Next, it was transferred from the camera to a computer, where it was selected as visually interesting, probably out of hundreds of alternatives. At some point, Dana wrote captions describing who and what was depicted in each of his selected photographs. Then it was edited, exported, and emailed to the Associated Press. There, a social media manager chose it to get published on Instagram as part of their coverage of the war. Finally, it showed up in my news feed between an ad for Flaming Hot Cheetos and a photo of a friend’s dog dressed in a tutu and tiara.

I was struck by the distortion and recontextualization of the photograph from Dana’s lens to my feed. Did Dana consider the various ways a global audience would experience his pictures? Did Oleg Mezhiritsky and Lidiya Mezhiritska know that their faces would be on millions of viewers' devices the next day? Would the viewers pause or scroll past their photo looking for more exciting content?

Even though I will never know the answers to my questions, I am still responsible for grappling with the images I experience and developing a purposeful relationship with them. My process involves hours at my easel painting.

Precipice reflects my experience of the fragmentation of the image, existence, and narrative of Oleg Mezhiritsky and his mother, Lidiya Mezhiritska.

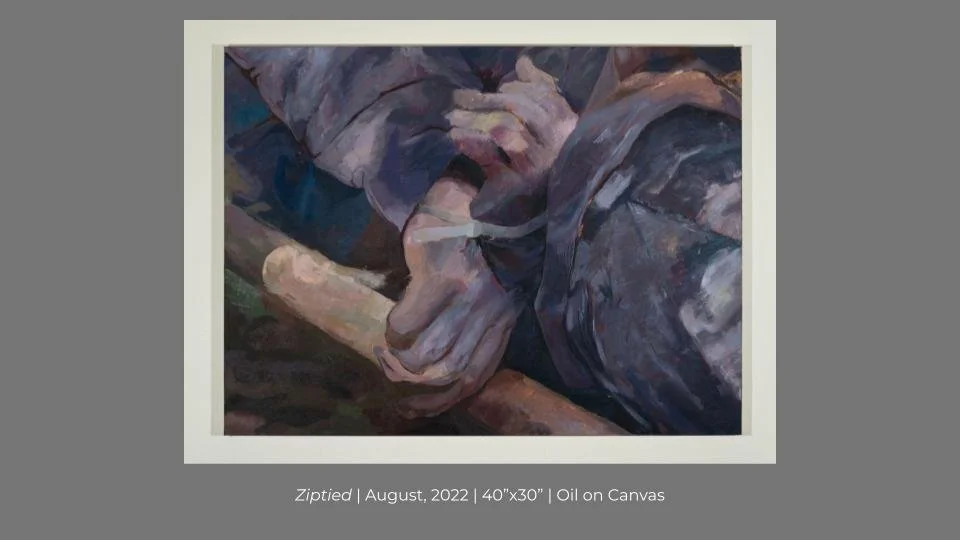

Ziptied

40"x30"

Oil on Canvas

August 2022

I painted Ziptied in response to a photo by AP photojournalist Efrem Lukatsky captured on April 4, 2022. The photo shows the discolored hands of a dead civilian with his hands zip-tied behind his back. This body was one of many recovered after the withdrawal of Russian troops from Bucha, Ukraine. According to local authorities, investigators have recovered 458 bodies from the town, including nine children under the age of 18.

This photo encapsulated an experience of captivity created by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. On the most obvious level, the man pictured was one of the hundreds of Ukrainian civilians in Bucha captured, tortured, and killed by the occupying Russian soldiers. Suddenly, his movement was constricted, and life was cut short.

From another perspective, he was once again captured and constricted by the photographer’s camera. The close-up photo of his hands is intimate enough to help the viewer identify his humanity––what can be more personal than one's hands––while remaining anonymous enough to help him stand in as a symbol of the many civilians killed in the conflict. There are now identifying marks, such as a wedding ring, to help the viewer piece together more of his story. The hands are withered and discolored from exposure, making his age and occupation a complete mystery. Even his gender can only be discovered from the Associated Press’s caption accompanying the image.

The subject's anonymity allows the news media to use this photograph symbolically. It becomes a visual icon standing in for the atrocity acted out by Russian soldiers on Civilians in Bucha, Ukraine. But its symbolic status can only be achieved at the cost of the subject’s personhood.

Lastly, I felt captured as a spectator of the horrors in Bucha. There was nothing I could do to help––nothing I could due to turn back time, stop the invasion, or give these bodies their breath back. As Susan Sontag writes, “Compassion is an unstable emotion. It needs to be translated into action, or it withers.” She goes on to warn that when spectators are consumed by their powerlessness, they get bored, cynical, apathetic.

I am still struggling with the difficulty of remaining sensitive and receptive to the suffering of anonymous others when it seems like their fate is so completely detached from my choices.

Still Life With Yellow Bag

30"x48"

Oil on Canvas

September 2022

I painted Still Life with Yellow Bag in response to a photo taken by AP photographer Efrem Lukatsky on April 6, 2022. The photo shows an elderly woman in a blue coat with a white shawl tied over her head carrying a full yellow plastic bag down a road in front of the ruins of apartment buildings destroyed by Russian Shelling.

The perspective of the photo is close to eye level, and the angle of the road, trees, and apartment buildings are slightly askew, giving the photograph a candid feeling.

The subject and her location speak to the destructive power of modern warfare and the cost that has on local civilian populations, especially vulnerable demographics like the sick or elderly. Everything about this image is designed to spark empathy in the viewer by building a bridge through space and time—making them feel like they know the story of the woman and have, at least imaginatively, experienced her circumstances.

The caption tells us the photo was taken in Borodyanka, Ukraine, but it doesn’t provide the woman’s name, where she is going, what is in her bag, or whether she was aware that she was being photographed. The anonymity of the elderly woman and lack of context in the caption creates a contradiction between the intimacy of the photo and its silence.

I tested the limits of this photograph by going to a local used clothing store and finding similar items to those the woman was wearing in the photograph. Could I build a bridge through to the woman by bringing her into my studio? I hung the items together and photographed them. Then I used the photo as a reference for a painting.

Rather than a genuine connection being made, I was left with the feeling of an uncrossable chasm between the woman pictured and me. Viewing her photo or recreating her wardrobe in my studio couldn’t bridge the gap between our worlds or transfer her experience to me.

By painting Still Life with Yellow Bag, I came to the conclusion that news photographs can lend a sense of immediacy to the stories we read about global conflicts. However, they can only share specific and limited fragments of time and space and shouldn’t be over-relied on to create connections or participate in the experiences of others.

Germ

36"x36"

Oil on Canvas

September 2022

I painted Germ in response to a screenshot I took of my Instagram feed on September 9, 2022.

There are times, like while I’m waiting to pick my kids up from school, that I’ll scroll social media to catch up on the day's news, get inspiration from fellow artists, and see what my friends and family are up to. My Instagram feed tends to be pretty eclectic since I follow the usual suspect––friends, family, and local businesses–– as well as a wide variety of artists, galleries, nonprofits, news outlets, and war correspondents. Throw ads and suggested posts into the mix, and it's easy to see how varied the content can be.

Due to Wyoming’s poor cell reception, my feed is sometimes filled with nothing but blurred photos with a thin white loading circle in the center. The photo would be unrecognizable for a few seconds, then the loading ring would disappear, and the photo would materialize.

I found this experience to be both nerve-wracking and intriguing. Would the loading image be a snapshot of someone’s morning coffee or an aerial photo of a bombed school in Ukraine?

Each blurred image was the embryo of something horrific, banal, uplifting, confusing.

It made me realize how much images shape my perception of what was real and what was possible. Through images, we create our collective reality, remember the past, and envision potential futures.

In the few seconds I waited for each image to load, I found myself desperately hoping for good news––babies born, diseases cured, prisoners released, conflicts ended––instead of the ongoing coverage of yet another land war in Europe.

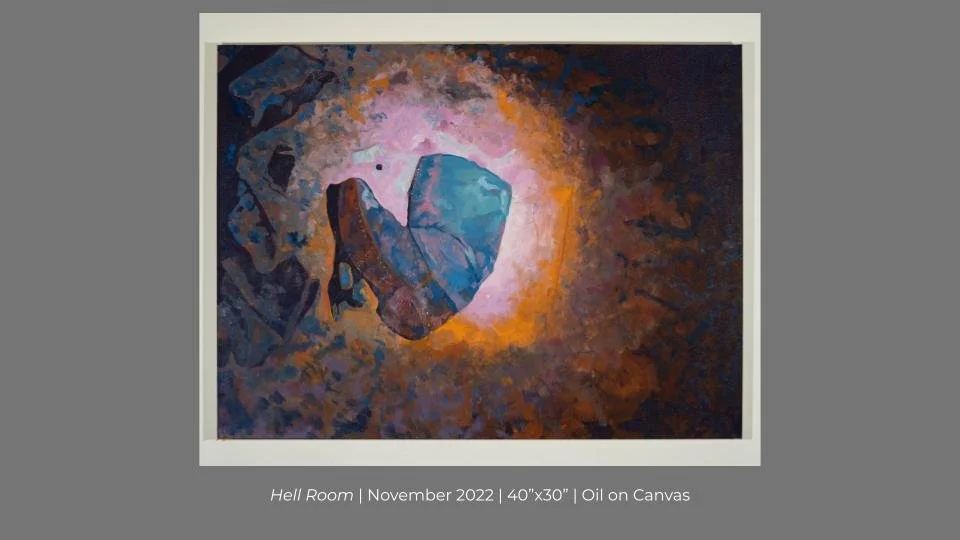

Hell Room

40"x30"

Oil on Canvas

November 2022

I painted Hell Room in response to a photo by Nikolay Onishchenko taken in 2017 of a pile of discarded firefighters' clothes in the basement of Hospital No. 126 in Pripyat, Ukraine.

Hospital No. 126 was where firefighters were taken after responding to fires at the Chornobyl Nuclear Power Plant on April 26, 1986. Their uniforms were so radioactive that hospital orderlies dumped them in a room in the hospital's basement. Their uniforms still emit 1,500 microsieverts of radiation an hour, making the room where they are stored one of the most radioactive places on earth.

When Russian troops occupied the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone, they used bulldozers to build bunkers and trenches where soldiers stayed for a month, breathing in radioactive dust.

This seeming insensitivity to the lingering effects of radiation calls into question our ability to learn from past mistakes. How can we, as a global community, leave the specter of nuclear radiation behind us if our thirst for a quick and decisive victory eclipses the value of every human life?

On January 24th, the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists — a nonprofit organization made up of scientists, former political leaders and security and technology experts — moved the hands of the atomic doomsday clock 10 seconds forward to 90 seconds to midnight.

Our fear over the approaching end of the world isn’t new. The same was true for our religious European counterparts who, before the year 1000, believed the Second Coming of Christ was imminent and the end was nigh. They would go on pilgrimages to famous churches housing religious relics to get right with God and demonstrate their religious devotion.

I painted this radiated boot as a contemporary relic, reminding us of our pride and ignorance and blessing us with the knowledge of how our scientific mastery and technological advancements may destroy us.

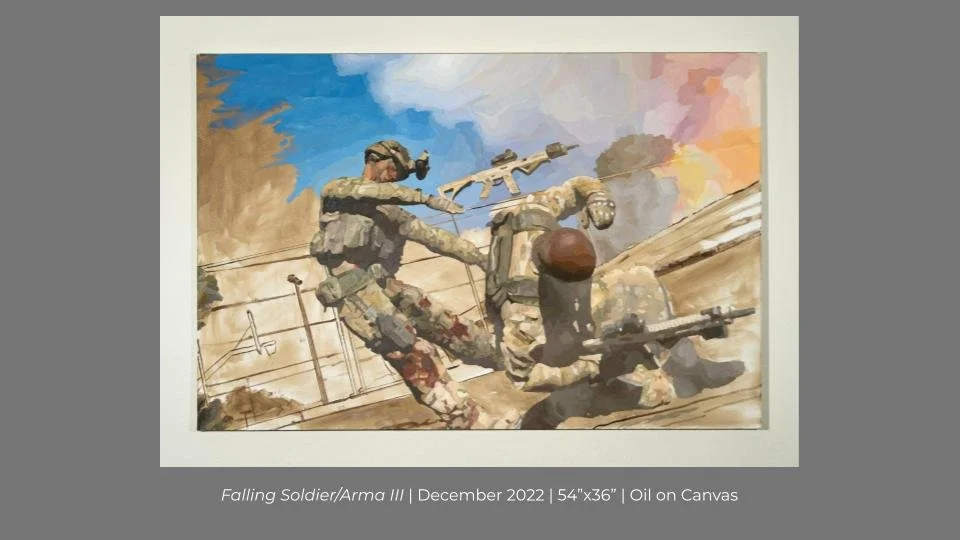

Falling Soldier/Arma III

54"x36"

Oil on Canvas

December 2022

TikTok’s policy on firearms reads as follows: “We do not allow the depiction, promotion, or trade of firearms, ammunition, firearm accessories, or explosive weapons.”

During the first months after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, TikTok apparently forgot they had ever censored content with weapons. The platform was swamped with video clips of missiles falling over the city of Kyiv like fireworks, drones dropping grenades into trenches filled with Russian soldiers, and Ukrainians blowing up tanks with U.S Javelin missiles. So many videos of the conflict were uploaded daily that a New Yorker article on March third dubbed it “the first TikTok war.”

Rather than the somber photojournalism and “just the facts ma’am” reportage of the press, TikTok videos followed another guiding principle: whatever gets the most attention wins.

The user-generated content, mostly shot on cellphones by Soldiers and civilians engaged in the conflict, demonstrates the aesthetic norms of TikTok: choppy, decontextualized, with catchy pop music in the background. The quantity and quality of footage made it hard to distinguish between contemporary verifiable footage and clips from prior conflicts, military training exercises, movies, and even video games. Many users and even some news outlets created sizzle reels combining all of the above indiscriminately, allowing them to amass millions of news in a few hours.

US Senator Hiram W Johnson is remembered for observing, “The first casualty when war comes is the truth.”

Where all these video clips came from seemed less important to their creators than the narrative being constructed and shared, casting the Ukrainians as desperate freedom fighters defending their homes against the evil Russian invaders. The problem is that history doesn’t comfortably conform to simple narratives with clear heroes and villains.

I painted Falling Soldier/Arma III based on a screenshot from the video game Arma III. It reminds me that the narratives we tell each other and the images we make are our own constructions, even when we call them “the truth.”

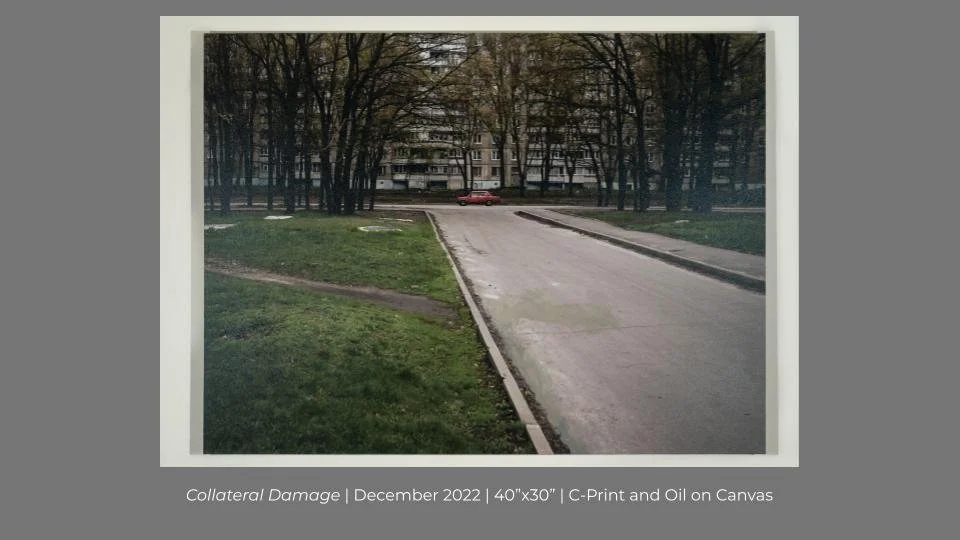

Collateral Damage

40"x30"

C-Print and Oil on Canvas

December 2022

I created Collateral Damage by first printing, then painting over a photo by AP photojournalist Felipe Dana captured on April 19, 2022. Dana’s photo showed the body of a man with white hair killed during a Russian bombardment of a residential neighborhood in Kharkiv, Ukraine. The man lies facedown in the street with his arms pinned under him. A trail of his blood fills the gutter.

Although Russia has staunchly denied it, evidence, such as this photo, shows how they have regularly targeted civilian neighborhoods in an effort to terrorize them into surrender.

The man in Dana’s photo was killed by a shell containing small darts called fléchettes. Each shell can contain up to 8,000 fléchettes. Once fired, shells burst when a timed fuse detonates and explodes above the ground.

Fléchettes, typically between 3cm and 4cm in length, release from the shell and disperse in a conical arch about 300m wide and 100m long. On impact with a victim’s body, the dart can lose rigidity, bending into a hook, while the arrow’s rear, made of four fins, often breaks away, causing a second wound.

How do we process such shocking and horrifying information? How do we move past it and try to live our lives once again? How do we live and work in spaces where such horrors have occurred?

It is human nature to grieve a loss and let time heal our wounds. It is also human nature to too quickly look away from painful realities. There is a reluctance to return to the scene of a crime.

Finding ways to process trauma and heal while still remembering with clarity the trauma that occurred feels, at times, impossible. Sometimes, as humans, it is our duty to struggle with the impossible.